Mix It Up: How to Accelerate your Learning with Mixed Practice

Mixed practice, the process of interleaving problem types and skills, leads to more effective learning even though it feels awkward. In this post I present the key strategies needed to implement it in your learning.

“The mind is exercised by the variety and multiplicity of the subject matter.” - Quintilian

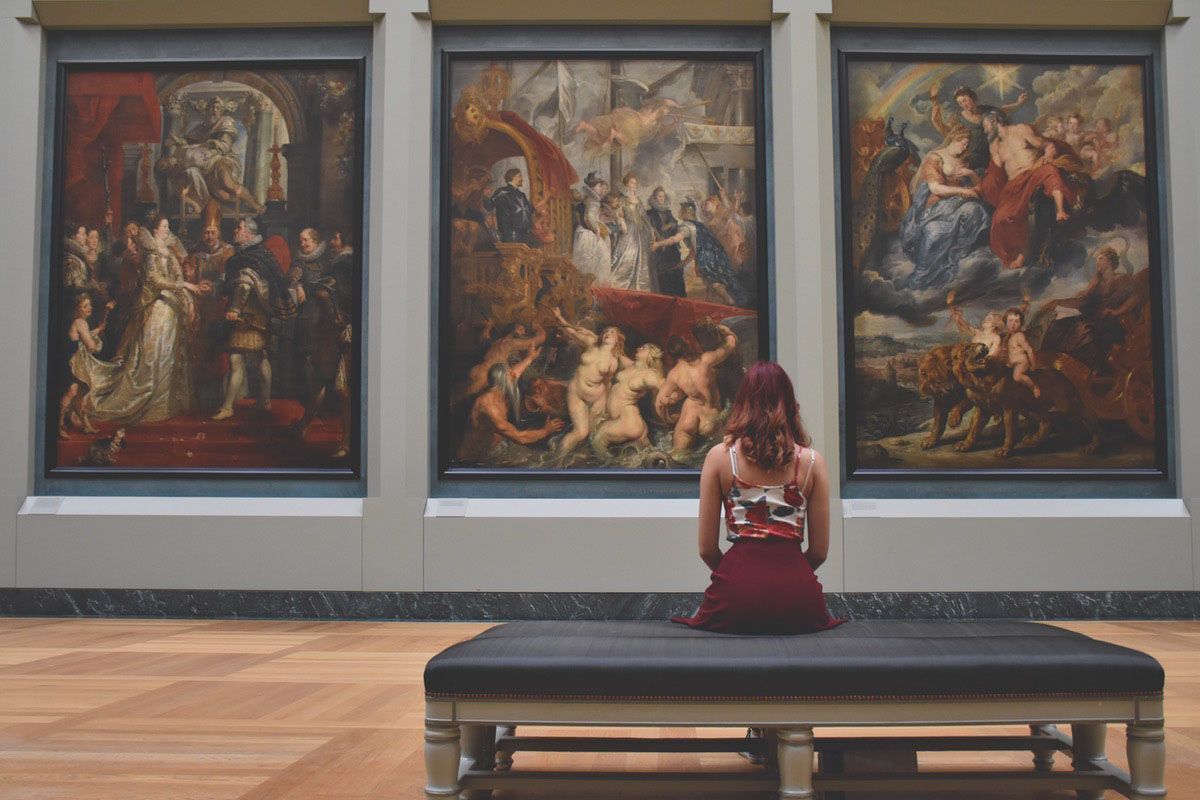

The Art of Learning

Appreciating art is a part of our culture that polarises people. Some love nothing more than to spend a long afternoon in a gallery, walking leisurely between paintings and discussing the depth of colour and texture of brushstrokes.

Others feel that spending more than five minutes at an exhibition is one of the greatest punishments known to man and see art appreciation as pseudo intellectual nonsense.

Whichever side of the spectrum you lean towards, art appreciation has provided a remarkable insight in to how we learn, providing us with actionable strategies that we can use whether we’re learning to play the guitar, improve our geometry or level up our golf swing.

In a 2006 study, renowned cognitive psychologist Robert Bjork and postdoctoral student Nate Kornell decided to test whether blocked or mixed practice worked better in identifying the works of painters.

That is to say, they tested whether studying many examples of one artist’s works before moving on to the next one worked better than studying all the artists’ paintings randomly.

Bjork and Kornell chose a collection of paintings by 12 landscape artists, and had 72 undergraduates study the paintings on a computer. Each painting was shown on the screen for 3 seconds along with the relevant artist’s name.

The undergraduates were split into two groups with the first studying the artists one at a time (3 paintings by Braque, 3 by Seurat, 3 by Cross) while the second studied them in random order (1 Cross, 1 Seurat, 1 Cross, 1 Braque etc.)

Mixed practice wins…or does it?

After the study period, the students were tested – they were asked to identify the artist for 48 unseen works, done by the same artists they’d studied previously.

The mixed study got group got 65% of the artists correct while the blocked group scored only 50%, proving the superiority of mixed practice. This clearly should have convinced the students that mixed practice was the better strategy.

Except that it didn’t. In a questionnaire after the test, Bjork and Kornell asked the students which method they thought was more effective.

Even though they’d performed 15% better on average with mixed practice, nearly 80% thought that blocked study was as good as, or better than mixed study.

There’s no such thing as a new idea

Bjork and Kornell’s results inspired a series of studies in piano playing, geometry, bird watching and batting in baseball, all of which have shown the superiority of mixed practice to blocked practice.

However, it’s important to recognise that these ideas aren’t new – they just haven’t been applied broadly across all disciplines yet.

Musicians often split their sessions between scales, playing familiar pieces and reading new music.

Athletes in team sports like football or basketball spend practice sessions working on position specific skills along with team skills in practice matches.

By experimenting with different methods, musicians and athletes have discovered the benefits of mixed practice by trial and error.

Now that cognitive scientists are proving its effectiveness in replicable research studies across a number of fields, we should all be looking to add more mixed practice to our own learning projects and seeing how it works for us.

Why don’t we mix it up more?

Mixed practice improves your ability to discriminate between problem types and choose the right solution.

This improves performance in tests and real world situations, where different problems appear randomly and we have to adjust on the fly.

Not only do we start to recognise the different types of locks better, we start to choose the right keys for each one. So why is the method so rarely used?

Just as with methods such as testing (retrieval practice), spacing and elaboration, more effortful learning is deeper and more durable.

Mixed practice feels less effective than the traditional blocked strategy of “practice, practice, practice” but it’s far superior in the long run.

This is shown by the response of the participants in Bjork and Kornell’s study on recognising artists, who continued to believe blocked practice served them better after the test.

To quote John Dunlosky, psychologist at Kent State University, who showed that mixed practice was more effective in differentiating between bird species, “People don’t believe it, even after we show them they’ve done better.”

The Takeaway

Most learners use blocked practice to focus on one problem type or part of a skill, wanting to master it completely before moving on to the next step.

However, the research shows that mixed practice, the process of interleaving problem types and skills, leads to more durable long-term learning even though it feels more awkward and less effective than blocked practice.

Try This

1) Practice skills together

Instead of focusing on one skill at a time, throw as many of your skills into practice sessions as you can.

For example, in tennis don’t spend separate sessions on your groundstrokes, net game and serve. Instead throw the skills into all three sessions and play some competitive points where you have to use them at unexpected times.

2) Override the textbook

Most textbooks are structured into chapters covering specific topics, with related review questions at the end of the chapter.

Instead of following the textbook structure, add different types of questions from other chapters into your review sessions. If you’re studying maths, throw in some calculus problems while you’re studying geometry.

3) Fight Your Intuition

Mixed practice will feel ineffective compared to blocked practice and you won’t look as good to spectators. Basically, you’ll look more like an amateur for longer, but this shouldn’t concern you if your goal is to learn as effectively as possible.

Ignore any embarrassment, trust the method, measure your performance through self-testing and you’ll see great results in the long run.