The Question is the Answer Part 2: Why We Stop Asking Questions and How to Start Again

As children we’re question generating machines, asking about forty thousand questions between the age of two and five. But then, something happens and the number of questions we ask falls off a cliff. In this article I explore the reasons why we stop asking questions and how to start asking them aga

"I am just a child who has never grown up. I still keep asking these 'how' and 'why' questions. Occasionally, I find an answer." Stephen Hawking

Why do we stop asking questions?

To answer that you need to ask another one.

Why do we ask questions in the first place?

We ask questions to understand the world around us and our place in it.

Questions drive us to open doors to new rooms, shine light in dark corners and turn over fresh pages.

They help us find out what might happen next, what happened before and what is happening right now.

Questions take us from a place of not knowing to a place of knowing.

That’s why, as children we’re question generating machines. We don’t know and we want to find out.

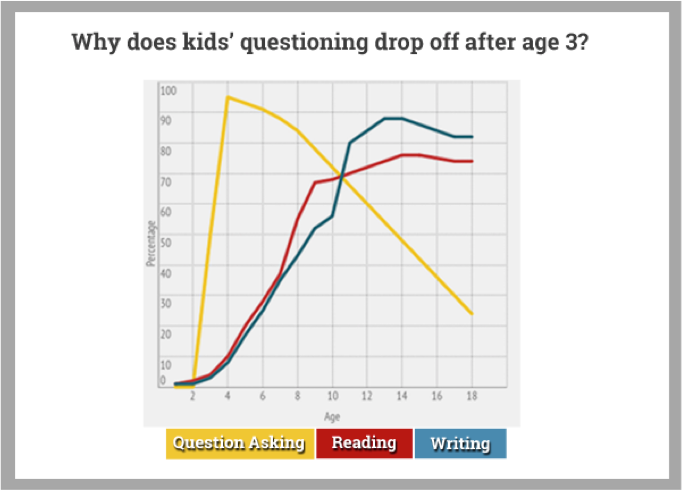

Research by Harvard child psychologist Paul Harris suggests that a child asks about forty thousand questions between the age of two and five.

The number averages out at around 100 questions per day but then, something happens. The number of questions we ask falls off a cliff.

By around the age of 11 most children have more or less stopped asking questions any at all.

Which takes us back to the original question. Why do we stop asking them?

One explanation is neurological.

After the age of 5, the brain starts to trim some of the neural connections that expand so quickly in the first few years of a child’s life.

This process of synaptic pruning could explain why children start to wonder less about the world and question it less as a result.

Another explanation is cognitive.

As we develop more mental models, we get better at categorising things. We know that an apple is an apple and a table is a table.

We have less need to ask questions like “What’s this?” and “What’s that?”

But this isn’t sufficient to explain the dramatic drop off in questioning.

Contrary to what a lot of commentators are currently saying, we do actually need to teach a certain number of facts for foundational knowledge.

But we shouldn’t teach facts so rigidly that we stamp out questions.

Our schools are optimised for putting as much information into the heads of students as possible so they can regurgitate it in an exam and meet certain predetermined standards.

Unfortunately this has been taken to such an extreme that there is very little time and space for questioning - because it’s not efficient.

Of course some questions are a waste of time in isolation...but if they help to generate another question then they’re no longer a waste – they’re a step along the path to discovery.

We seem to have forgotten that learning doesn’t always need to be efficient to be effective. It is not a linear process where you pull lever A and pump out widget B.

In fact some the most remarkable and significant kinds of learning are highly inefficient.

How do we start questioning again?

I remember going through various times in my life where I’ve stopped questioning the world around me.

Invariably these have been times where I’ve chosen to focus on a specific project like acing my final exams at university or producing the video course for MetaLearn.

And the truth is that in order to do something difficult, you need to prioritise acting on existing knowledge and experience, rather than gathering more.

Computer scientists describe this as exploring and exploiting – a computer system can learn more if it explores more options but it will be more effective if it simply picks the most likely one and acts on it.

Think of exploring and exploiting as a spectrum: on one end we have an endlessly curious but ultimately ineffective Peter Pan character; on the other we have a tremendously dull but highly effective square.

It’s obvious that we need to strike a balance between these poles at different times in our lives, depending on what our goals are.

But the truth is that as adults, we often stray towards the side of exploiting the existing knowledge and habits we’ve developed, rather than continuing to inquire and learn. We get complacent. We think we know. And we stop asking.

The 3 steps you need to rediscover to start questioning again are:

1) Accept Your Ignorance

Without an acceptance of your own ignorance and an awareness of what you don’t know, you won’t ask good questions that will help you learn new things.

Scientists who are often seen as the people in our society with all the answers are actually the ones who are most aware of what they don’t know. What they’re actually good at is asking questions as author Stuart Firestein points out.

In his book Ignorance: How it Drives Science, he writes “One good question can give rise to several layers of answers and inspire decades-long searches for solutions and generate new fields of inquiry. Answers on the other hand, often end the process.”

2) Use Your Imagination

Once you’ve accepted that you don’t know much, you need to be able to conceive of a possible answer...or several of them.

The tool that will help you do that is your imagination, which according to Darwinian theory, we developed many millennia ago as a survival mechanism to cope with the inherent uncertainty of the world around us.

The ability to envision possible situations before encountering them enables us to build mental maps of the future and explore them before choosing our path forward.

The key to using your imagination is simply letting it run wild – don’t filter yourself and come up with as many ideas as possible.

3) Seek Out People

One of the things that separates us from other animals is our ability to form and use complex language to communicate.

This remarkable technology of language allows us to imitate, copy and learn from each other; to transfer knowledge, ideas and practices from one mind to another.

Once you realise that so many of the things that you want to learn already exist inside a human being, the solution becomes remarkably simple.

Go and seek out those who you want to learn from. And fire away with the questions.