Overcoming the Fear of Public Speaking: 3 Strategies from the Ancient Greeks on The Art of Rhetoric

Many assume that good speakers possess an intrinsic talent and that their own skills can’t be developed. This just isn’t true. In fact, the formal study of public speaking began around 2,500 years ago in Ancient Greece to train citizens to participate in society. This post will take you back to the

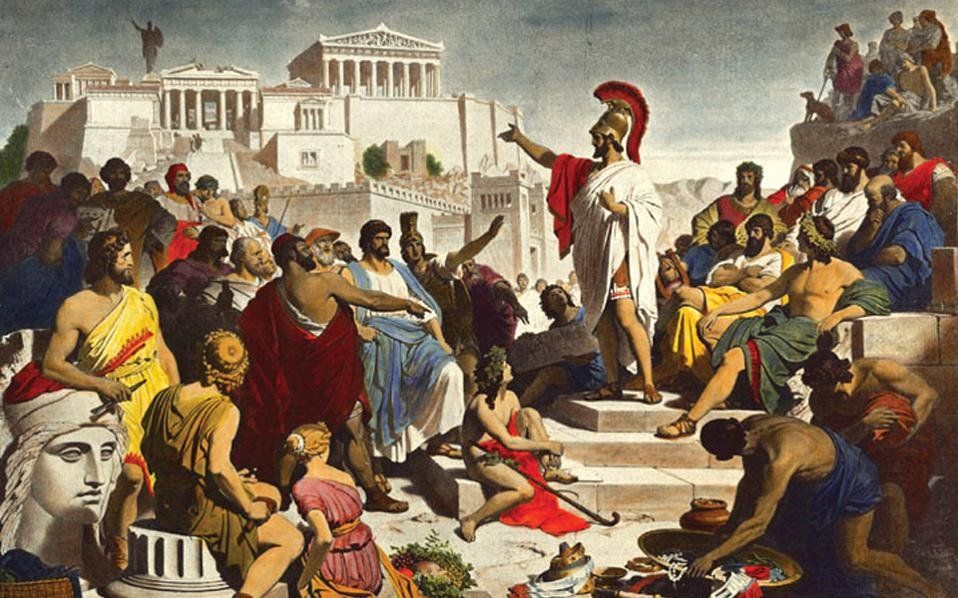

Pericles' Funeral Oration by Philipp Foltz (1852)

It’s almost your turn…

You can feel that familiar hollowness in your gut and your heartbeat starts to quicken.

The voice in your mind starts to pipe up: What happens if I forget everything? What if I look stupid? And what will they all think of me?

Small beads of sweat are forming under your hairline and the back of your neck and your clothes suddenly feel a size too tight, gripping your skin as the tension builds.

It’s common knowledge that public speaking is terrifying for almost everyone.

In fact surveys about our fears commonly show fear of public speaking at the very top of the list above death! Whether you’re pitching your product or service to potential buyers, presenting to your colleagues at work or giving a speech at a workshop, you’ve probably felt this before yourself.

You know the fear is totally irrational, but even when you’re aware of this, you still feel the fight or flight response taking over.

Of course, these feelings may have been useful in the past as social psychologist Elliot Aronson notes in his book The Social Animal. Exclusion from a group in those times would almost inevitably lead to death so anything that threatened our status would set alarm bells ringing.

The legacy of this instinct is that standing out by getting up to speak in front of others creates a "me and them" dynamic that feels like a huge risk even if it’s actually trivial.

If you mess up a speech the worst that will happen is that a few people will laugh (often out of their own insecurity about public speaking) and everything will be forgotten by tomorrow.

Mark Twain, the originator of many a pithy quote once said “there are two kinds of speaker: the one who’s nervous and the one who’s a liar.”

Twain was right on the money with this, because even the best public speakers – the ones you see nailing TED talk after TED talk have described how nervous they feel before speaking.

Lloyd George who was the British Prime Minister during WW1 and is still considered by many to have been the greatest orator in British history (even greater than Churchill) was said to have admitted to feeling sick and pacing around nervously before he had to speak in the House of Commons.

And if they didn’t go away for the Prime Minister of Great Britain, these feelings will probably never go away for you either, as long as you have a fully functioning nervous system!

Fortunately though, you can prepare yourself to deal with it, so that when your time comes, you can deliver your message clearly and powerfully to your audience.

Speaking Skills Can be Learned

Not everyone can go down in history as a master orator, but we can definitely all learn to improve our spoken communication.

So many assume that good speakers possess an intrinsic talent – the so-called gift of the gab - and assume that their skills can’t be developed and improved.

This just isn’t true. In fact, the formal study of public speaking began around 2,500 years ago in Ancient Greece to train citizens to participate in society.

So it seems only fitting to go back to the source and extract the wisdom of the Greeks to help you improve your own public speaking skills. Here are three strategies from three master orators on the preparation, practice and content of your speech.

***

1) Pericles on Preparing

"Having knowledge but lacking the power to express it clearly is no better than never having any ideas at all." - Pericles

The statesman, general, and master orator Pericles ushered in a golden age of eloquence during his rule of Athens from 461-429 BC.

His funeral oration was the first great speech to be written and prepared for the general public, and set the standard for all orators that came after him.

A master strategist on the battlefield who won many a successful expedition, Pericles also prepared meticulously for his oration.

The first thing Pericles considered before preparing any speech was to begin by thinking about the purpose. During the preaparation phase, you should ask whether you’re you trying to inform (like in a lecture), persuade (a debate or pitching contest) or entertain (like a best man speech at a wedding).

Next Pericles would try to summarise the essence of his talk in one simple sentence. Be aware that your audience will usually leave with one thing and one thing only, so be intentional about your core message. Otherwise they’ll leave with nothing!

Finally Pericles would reflect on the audience he was presenting to – the citizens in the agora or a gathering of noblemen at a private council. When you’re preparing you should consider who your audience is and will need to adjust for according to profession, demographics and interests.

So ask yourself - what’s your objective, what’s your message and who’s your audience? If you can answer those questions in your preparation, you’ll be streets ahead of most people already.

Once you’ve got that clear, build a skeletal outline of the speech that contains the key points and evidence or stories that illustrate them without writing them word for word

Remember, you never want to try to remember your speech verbatim because you’ll either get thrown off track very easily or will end up sounding overly mechanical.

Instead just think of the main points you want to touch on and what sequence you want to hit them in.

2) Demosthenes on Practicing

"As a vessel is known by the sound, whether it be cracked or not; so men are proved, by their speeches, whether they be wise or foolish." - Demosthenes

Demosthenes was one of the greatest orators of all time, someone who could hold a crowd in the palm of his hand.

But he didn’t get there by having an easy ride or by being naturally gifted. Instead he was faced with countless obstacles and challenges.

The problem was that he was not only frail and socially awkward but he also he suffered from a severe speech impediment, which he was constantly ridiculed for.

But, instead of allowing these obstacles to hold him back, Demosthenes used them to fuel his motivation and resolved to work harder.

He spent hours practicing his skills in the swirling wind to improve his delivery; he practiced speeches with pebbles in his mouth to improve his articulation; he even shaved half of his head so that he’d be too embarrassed to spend time in the outside world and more time practicing his speaking in a cave.

Despite all his disadvantages he faced and a clear lack of natural ability. Demosthenes found a way. And he found it through repeated practice. This process may not be linear but one thing is for sure – if you don’t keep speaking, you won’t improve.

In terms of where to start, I recommend throwing yourself into it – if you’re just looking to improve your skills over time go and join a local Toastmasters club or any other public speaking Meetup event.

If you can, ask someone to film you from time to time so that you can get objective feedback and notice your good and bad habits.

It’s very easy to spend too long over-analyzing when it comes to public speaking so make sure you start sooner rather than later.

If you’re just practicing for a specific speech or presentation you can try ita few times in front of friends or family, but this is less preferable to doing it at a club or meetup because you’re less likely to feel like it’s the real thing and you’re also less likely to get honest and useful feedback.

The key is to simulate the exact environment you’ll be in as accurately as possible – if you have access to the same room, use it. If you’re going to be using slides or visual aids, make sure you practice with those.

3) Aristotle on Content

“There are, then, these three means of effecting persuasion. The man who is to be in command of them must be able to reason logically, to understand human character and to understand the emotions." - Aristotle

Aristotle is considered by many to be the greatest philosopher of all time.

A student of Plato, Aristotle wrote works on all the natural sciences and all branches of the arts and philosophy but still found the time to found his own school, tutor Alexander the Great and go for plenty of long walks!

A particular area of expertise for Aristotle was rhetoric – he certainly knew how to persuade and get his point across both in lessons with students and debates with peers.

He believed that any good persuasive speech should be built on the three fundamental building blocks he outlined in his work “Rhetoric” – ethos, pathos and logos.

A) Ethos

Ethos is about demonstrating that you are trustworthy and likeable, and are qualified to speak about your subject of choice. The best ways of doing this are through stories, which preferably employ humour – if you can self deprecate then you’ll be the better for it.

Another technique is to downplay your abilities, causing your audience to dismiss this as false modesty. And finally, you can associate yourself with others whose qualities you’d like your audience to attribute to you.

B) Pathos

Pathos is about rousing the emotions of your audience to create an environment that is receptive to your message. You can do this by considering the fundamental desires of most human beings – freedom, importance, pleasure, connection, community, growth and contribution.

If you can use colourful and emotion based stories that genuinely move the listener and appeal to these desires you’ll be well on your way to delivering powerful persuasive speeches.

C) Logos

Finally, once you’ve established your own credentials and created a receptive emotional state in your audience, you can deploy logos – the structured use of reasoning to persuade your audience. In order to do this effectively, your reasoning must be kept clear and your argument short.

Any additional complexity is harming you rather than helping you, even though it may seem that the more jargon and technical words we throw in the better at times. Reasons and arguments will have far less force if your listeners aren’t already disposed to move emotionally in the direction that they try to justify.

***

So there you have it – 3 essential public speaking lessons from the Ancient Greeks that you can apply straight away.

Now I’m well aware that not everyone needs to deliver a public speech or become a master orator. Unless you’re a politician, actor, start-up founder, teacher or some other public figure, you may not even have to do this type of speech all that often.

But ideas are the currency of the 21st century and in my book, being able to present them effectively is a skill that everyone should spend some time on.

We’re definitely living in a time where being able to speak effectively can give you a whole lot of credibility.

First because any speech be recorded and broadcast to potentially millions of people over the internet – just look at the mercurial successes of some TED speakers following a powerful speech.

And second because so few people are actually willing to do it, which really makes you stand out if you take the opportunities that come your way.